ShareThis is disabled until you accept Social Networking cookies.

From the vault: “Double World Champion”

Though it’s often a contentious topic, most fans of Indy car racing can agree that the sport reached a commercial and popular peak in the first half of the 1990s. The Month of May and the Indianapolis 500 remained strong, but Championship Auto Racing Teams (CART) had elevated the rest of the Indy Car World Series from a poorly-promoted patchwork of second-tier events propping up Indy into a successful, year-long series on a national and increasingly international basis.

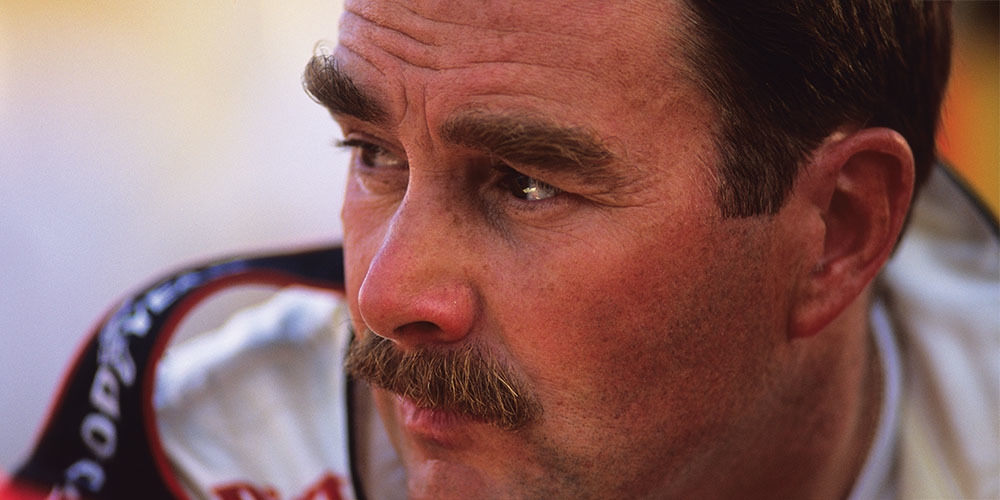

Many CART-era supporters would go on to argue that the 1993 season was the absolute apex. Spurned by the Williams-Renault team, newly crowned Formula 1 World Champion Nigel Mansell committed to contest the full PPG Indy Car World Series season for Newman/Haas Racing, sliding into the well-developed Lola-Ford-Cosworth vacated by McLaren F1-bound Michael Andretti. The Indy/F1 driver swap was greeted with great fanfare…and one of the two men more than lived up to the hype.

That was Mansell. As dramatic, brave – and polarizing – as ever, he adapted quickly to oval racing and won the CART title at his first crack, a feat commemorated in Mark Knopfler’s song "Speedway at Nazareth." For a week in September, until Alain Prost clinched the 1993 F1 crown at the Portuguese Grand Prix, Mansell held the F1 and Indy car titles simultaneously and took to calling himself "Double World Champion."

But despite Mansell’s spectacular exploits on the track and larger-than-life personality, there was so much more to the 1993 Indy car season than just "The Ballad of Red 5." Blocking the Englishman’s path to the title were a cadre of Indy car veterans, led by Team Penske’s Emerson Fittipaldi (the 1972 and ’74 F1 World Champion, who’d made a successful career switch to CART in the ’80s); defending CART champ Bobby Rahal, owner-driver for Rahal-Hogan Racing and trying to develop his own chassis; Arie Luyendyk, in his first year with Chip Ganassi Racing; and the uneasy Galles Racing pairing of Danny Sullivan and Al Unser Jr.

There were also promising newcomers. Robby Gordon signed for a full season with A.J. Foyt after racing into CART part-time in 1992 with Ganassi’s young team. Canadian Scott Goodyear’s breakout ’92 campaign with Walker Racing included a win at Michigan Speedway and two other podiums. And fellow Canuck Paul Tracy was heralded as a can’t-miss prospect; the 24-year-old Penske development driver was in the right place at the right time to land one of the sweetest rides in the sport when Indy car legend Rick Mears unexpectedly announced his retirement in December ’92.

Lastly, there was Mario Andretti, the man whom the Newman/Haas team was built around, who was coming off four very satisfying seasons in a comfortable, familial environment with his son as his teammate. Mario knew Mansell from 1980, during his final year with Team Lotus in F1, and fair to say theirs was not a warm, fuzzy relationship…

Mansell, his wife Rosanne, and their children fully committed to their U.S. adventure, settling into a home in Clearwater, Fla. A huge contingent of F1 media covered his first Indy car test sessions at Firebird Raceway and Phoenix International Raceway, and the Indianapolis Motor Speedway rapidly doubled the size of its media center to accommodate the international interest.

Oddly enough, Mansell’s American odyssey actually flagged off in Australia, where CART’s season opened on a street course in Surfers Paradise from 1991 to ’94. Nigel hustled to pole position but, perhaps not surprisingly, made a mess of his first career rolling start. Dropping to fourth, he fought back to overtake Fittipaldi for the lead on the 16th lap, but the pass occurred where a local caution flag was displayed. No worries, mate, because Mansell combined a stop for fuel and tires with his black flag penalty three laps later (a practice now outlawed) and was soon back out front. Mansell won his Indy car debut by five seconds over Fittipaldi – a one-two of F1 champs – the Brazilian disappointed that a faulty fuel reading discouraged him from pushing harder.

After setting an unofficial track record at Phoenix in testing, Mansell’s confidence was sky high when he arrived at the Desert Mile for the race in April. Too high, because shortly into the second practice, the Newman/Haas Lola spun and pounded the wall with enough force to leave a gaping hole in the concrete. Concussed and suffering severe bruising to his back, Mansell flew home before teammate Andretti won the race.

Under the watchful eye of Dr. Terry Trammell, Nigel made the start a week later at Long Beach – again from the pole. In severe pain, he bravely battled to third in the race, surviving a clash with Unser Jr. on the way. But Mansell wasn’t the only driver racing hurt at Long Beach. Tracy, since throwing away certain victory at Phoenix, was also battered and bruised after flipping a gokart between races. "I was on thin ice with Roger [Penske] that weekend," Tracy told RACER’s Marshall Pruett in 2016. But he redeemed himself with a flawless first Indy car win on the California streets.

Luyendyk earned the first of his three career Indy poles, with speeds down about 9mph due to a narrower groove resulting from removal of the "apron" inside the turns. Mansell, 39 years old, yet a genuine rookie in terms of oval racing, put himself in position to win. But his lack of situational inexperience cost him the lead on a late restart, and he was beaten to third place by Fittipaldi and Luyendyk. Emerson caused a minor uproar when he drank Brazilian orange juice in Victory Lane after his second "500" win.

Mansell demonstrated how quickly he learns from his mistakes just a week later in the traditional post Indy stop at the Milwaukee Mile. He passed Raul Boesel for the lead with 19 laps remaining and held off the Brazilian during a late restart. Hugely brave, Mansell always excelled at fast corners in F1, and Phoenix crash aside, he adapted amazingly quickly to the unique skills required for oval racing.

"He was really extraordinary catching on to the ovals," said Jim McGee, the legendary crew chief tasked by Carl Haas with managing Mansell’s effort (not to mention Mansell himself) in 1993. "Nigel was a special guy who did a heck of a job. He was flat out his first year and he won all the oval races he ran except for Indy, and he should have won that. And he was a showman, a magnet for the press. It was tough on Mario."

The Detroit GP, in its second year at Belle Isle, was an anomaly. Fittipaldi and Mansell didn’t factor on race day, leaving Galles teammates Unser and Sullivan in a contentious battle resolved in Sullivan’s favor after he forced Al Jr. into an early version of a track limits penalty. It was Sullivan’s 17th and final Indy car win. Normal service was resumed in late June at Portland, where Fittipaldi beat Mansell in a straight fight, with Tracy third in his first finish since he won Long Beach.

The Canadian was still crashing all too often, most recently when leading at Milwaukee. But he collected himself to post consecutive wins in Cleveland and Toronto, hauling himself to fourth in the standings in what was becoming a two-man race between Fittipaldi and Mansell.

"Man, I was just a punk kid surrounded by F1 world champions," Tracy says now. "They were great times. We had 700-750hp, a standard tire from Goodyear, and pretty good aero. That’s when we had our best racing on ovals, before the cars started getting really fast."

Mansell added to his legend by dominating the Michigan 500 after complaining bitterly about the bumpy surface. He asked for aspirin in his drink bottle during the race and looked totally spent in Victory Lane. Andretti, fresh as a daisy after finishing second, was not amused…

New Hampshire produced one of the decade’s best Indy car races. Mansell hunted down Fittipaldi and then Tracy in the closing laps, whipping around Tracy on the outside to take the lead on Lap 197 of 200. The storybook triumph came on Nigel’s 40th birthday.

"I can remember that race very vividly," Mansell told this writer in 2003. "Overtaking Paul on the outside of Turns 1 and 2 and just slipping in there. There were just a few laps to go so he couldn’t respond. It was a great race and a super birthday present."

Following wins by Tracy at Road America and Unser at Vancouver, Fittipaldi pulled himself back into the title hunt by winning at Mid-Ohio after yet another wreck by Tracy when leading. But Emerson had no answer for Mansell on the Speedway at Nazareth, as Nigel led 154 of 200 laps on the frenetic, 0.946-mile tri-oval in Andretti’s Pennsylvania backyard to clinch the ’93 CART title.

A Penske 1-2 in the season finale at Laguna Seca led by Tracy, along with a Mansell DNF, reduced the final margin between Nigel and Emmo to a somewhat misleading 8 points.

Mansell’s achievement was remarkable. He had the benefit of stepping into a thoroughly competitive car, but then so did Michael Andretti in F1, where he earned just three points-scoring finishes in a McLaren that Ayrton Senna drove to five Grand Prix wins.

"Obviously, winning in ’93 was like dream come true – winning both world titles back-to-back was sensational," Mansell related. "I loved the time there. I think the people were great."

Unfortunately, Mansell vanished from the Indy car scene almost as quickly and with almost as much fanfare as when he arrived. He was tempted back to F1 by Williams after Senna was killed on May 1, 1994, and while he finished out the ’94 Indy car season with Newman/Haas, his motivation – and results – waned in the second half of the season.

From a business perspective, CART continued on its upward trajectory for the next few years, nurturing a new generation of talent on the way. But it never connected with the public again on a level like it did during that magical 1993 season – the year of Nigel Mansell, Double World Champion.

ShareThis is disabled until you accept Social Networking cookies.

John Oreovicz

John Oreovicz is one of America’s most versatile motorsports writers, earning respect over a 30-year career that includes stints with National Speed Sport News, Autosport, ESPN, and RACER. He has authored several racing-themed books, including the award-winning “Indy Split” (2021, Octane Press).

Read John Oreovicz's articles

Latest News

Comments

Disqus is disabled until you accept Social Networking cookies.